Research

Harnessing the Power of Community in Pursuit of Zero Suicide

Louis T. Joseph1,2, Chun-Yi Wu3, Denise Joseph1

- Open Sea Institute, West Palm Beach, Florida, United States

- Parrish Medical Center and Health Network- Mayo Clinic Care Network Member, Brevard County, Florida, United States

- Institute of Gerontology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States

Corresponding Author

Louis T. Joseph

Email Address: louisjosephmd@opensea.institute

Link to study: https://psyarxiv.com/wxu5k

ABSTRACT

The Zero Suicide movement is an international movement which aims to eliminate suicide by way of radical healthcare system redesign1. In early 2017, within Brevard County, Florida, an international hub for aerospace and home to the Kennedy Space Center, a community based task force was assembled to intervene when the pediatric suicide rate reached one of the highest rates in the State of Florida. Pediatric Mental Health was previously identified as a top priority on multiple community health needs assessments performed by organizations throughout the region. Within the ensuing 24 months, a community wide evidence based technical package to prevent suicide was implemented and the pediatric suicide rate was reduced to near zero, the lowest rate the region had seen in over 20 years.

Keywords:

Zero Suicide, Pediatric Mental Health, Community Based Interventions, Public Mental Health, Suicide, Suicide Prevention, Public Mental Health, Adolescent, Pediatric Depression, Pediatric wellness programs, Suicide Rate.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, the rate of suicide has continued to climb inside the United States2,3. Pediatric mental illness continues to take center stage as school shootings and other unfortunate outcomes related to mental illness are becoming commonplace in society and in the news media. Within this context, an international movement to achieve zero suicides has developed, catalyzed by the initial work within the Henry Ford Health System4,5. Despite the worldwide growth of the Zero Suicide movement, there continues to be a dearth of outcome studies measuring completed suicides in the various regions across the globe which have reportedly implemented the objective.

The State of Florida is consistently ranked among the lowest for mental healthcare expenditure per capita in comparison to other States6. Within Brevard County, Florida, the pediatric suicide rate for 2017 was one of the highest in the State of Florida and represented ongoing significant increases from prior years. Postmortem review of the suicide deaths indicated that the majority of these deaths did not have a health system contact in the months preceding the suicide. Pediatric mental health was identified as a critical priority on multiple community health needs assessments performed by organizations throughout the region7,8. Furthermore, the opioid epidemic had also taken its toll on Brevard County, leading Brevard to experience the third highest rate of overdose mortality within the State of Florida9. In this context, multiple members of the community called upon regional health network leadership, the newly arrived Health Network Chairman of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Services, to guide them in the pursuit of reducing pediatric suicide. Said leadership, assessed the situation and advised that elimination of pediatric suicide was within the realm of possibility. The Health Network Chairman introduced the concept of a Community Task Force and provided vision and advisement at every stage of its activity.

METHODS

The determined goal was straightforward and was selected by the community Task Force– eliminate pediatric suicide. Given the fact that most of the suicides did not have contact with a health system in the months prior to their deaths, it was determined that the intervention needed to be focused heavily within the community. Previously published Zero Suicide initiatives, on the other hand, traditionally functioned within the confines of the health system4,5,10.

The Task Force was initially comprised of numerous community activists, school teachers, concerned parents, students, and a few mental health system leaders who gathered together to discuss the problem. In the past, when such tragedies struck the community, there was a tendency to have town-hall discussions that did not lead to longitudinal, cross-sectional interventions that could systematically address a particular health outcome or social determinant of health. Upon advisement from the Health Network Chairman, it was decided that a town-hall type discussion was not the answer and the notion of an ongoing workgroup was introduced and agreed upon. The Task Force was initially led by the Health Network Chairman, an elementary school teacher, and a community activist. The preliminary undertaking was to determine the optimal composition of the Task Force given the overarching goal and the need to build upon existing momentum to further charge the community with the unique challenge of achieving zero pediatric suicides. Because the Task Force was completely voluntary and community based, the decision was made to welcome any person in the community who wanted to join but to also extend strategic invitations to leaders in various sectors across the region that had some ability to influence a child’s livelihood. Capitalizing upon momentum that was deliberately promulgated by community activists, invitations were sent to leaders within law enforcement, the school system, state legislature, the community 211 resource agency that provides referrals to health and social service organizations11, faith communities, municipal leadership, multiple healthcare organizations, health insurance organizations, the YMCA, and Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs. Initially most of the invited organizations agreed to have a representative join. In time, all of the aforementioned organizations joined the Task Force and participated to varying degrees. The Task Force also enlisted the volunteer efforts of a health system based six sigma black belt who guided the ongoing efforts in process improvement and assisted in facilitating select meetings.

The Task Force initially met monthly. After introductory meetings and a review of several approaches to target suicide in a community, the decision was made to utilize the 2017 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Technical Package entitled, Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policy, Programs, and Practices14. This evidence-based roadmap for transformation was ultimately chosen because of the heterogeneous composition of the Task Force and because of its emphasis on transformational change in a community versus a more narrowly tailored intervention housed within the healthcare system.

After selecting the roadmap, the Task Force divided into multiple committees based upon each strategy category of the 2017 CDC Technical Package14. Task Force members were asked to join committees based on their self-perceived ability to create positive change and contribute on the committee subject matter. These committees included the following:

- Strengthen Access and Delivery of Suicide Care

- Promote Connectedness

- Teach Coping and Problem-Solving Skills

- Identify and Support People at Risk

- Lessen Harms and Prevent Future Risk

- Create Protective Environments

- Strengthen Economic Supports

The committee meetings were held one to two times per month. Leaders of the committees were selected by the committees themselves or Task Force leadership and they were responsible for guiding the committee meetings and holding committee members accountable to action items that were developed. At the monthly Task Force meeting, each committee leader would report on the progress that their committee was making. Committee leaders would also utilize general Task Force meetings for ongoing support, further recruitment for their committees, planning, and quality improvement for committee initiatives.

Numerous interventions were undertaken by the Task Force. Some select examples of the many follow:

Strengthen Access and Delivery of Suicide Care

Task Force members successfully worked with health insurance organizations to include coverage provisions allowing home-based or school-based services for their members. Lack of transportation hindered many children from attending mental health related appointments. To target the problem of lack of transportation hindering access to care, a successful ride sharing initiative was developed and is now underway. Multiple Task Force members with key affiliations played roles in its design, funding, and implementation.

Identify and Support People at Risk

Numerous gatekeeper trainings were conducted within the community and school system. Task Force members participated in ongoing efforts working with the health system, standardizing pediatric mental health risk assessment across health settings and removing barriers to the communication of salient health information between health system and school system. Within the school system, substantial, ongoing changes were made to the timeliness and appropriateness of mental health screening, referral to services, and communication of salient health information internally and externally. The school system added staff and redefined the roles of select members of existing staff to focus more intensely on student mental health and wellness, removing said staff’s occupational emphasis from the administrative tasks with which they were previously burdened.

Promote Connectedness, Teach Coping and Problem Solving Skills

To serve the dual aims of promoting connectedness and teaching coping skills, the Task Force selected, funded, piloted, and assisted in the dissemination of evidence-based mental wellness programs and peer norm programs throughout the school system and in certain faith communities. Mental health experts from the Task Force also served as ongoing guides and collaborators for the school system as the school system further developed a Social Emotional Learning curriculum15,16.

Lessen Harms and Prevent Future Risk, Create Protective Environments

In order to lessen harms, prevent future risk, create protective environments, regional media outlets were utilized to provide ongoing coverage of Task Force efforts. Task Force members were also given the opportunity to write regular newspaper columns on topics related to mental health. The subject matters of the columns were deliberately crafted with the intention of dampening stigma and increasing help seeking behavior, drawing upon any available evidence-based data when formulating the content17. Social media was utilized to the same end. Student members of the Task Force played an ongoing active role in that domain.

Other Activities

Task Force members met with delegates from the Florida State Legislature to call on them to assist in the advancement of legislation that would support aspects of the CDC roadmap for the State of Florida. Legislature ultimately incorporated Task Force requests within legislation that was subsequently codified into law.

Next Steps

The work toward the roadmap is ongoing. Projects described above continue to be part of the Task Force efforts. Additionally, new targets continue to be developed. These include working with law enforcement agencies to utilize standardized-actionable suicide risk assessment tools, destigmatizing the involuntary commitment process, and working with not-for-profits towards the provision of affordable housing for those in need.

RESULTS

The outcome of this community wide effort was a substantial and significant 90% reduction in the pediatric suicide rate when compared to the startup year rate.

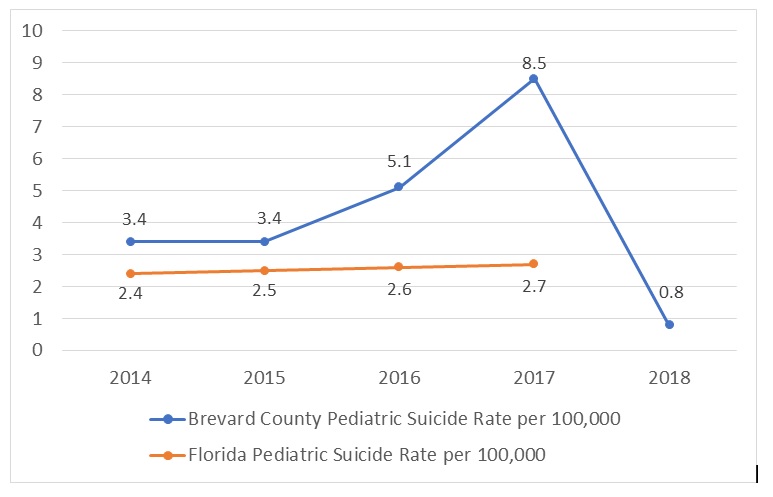

Figure 1. Pediatric Suicide Rate (Age 0-19) per 100,000 for Brevard County vs Florida

The observed pediatric suicide rate was 3.4 per 100,000 during 2014-2015 and it increased to 5.1 per 100,000 at baseline (2016).

At the start-up year (2017), the pediatric suicide rate was 8.5 per 100,000 and decreased to 0.8 per 100,000 in the follow-up year (2018).

Poisson regression was used to test the difference of suicide rate among pre-baseline (2014-2015), baseline (2016), start-up (2017), and follow-up years (2018). There is no statistical difference in suicide rate between pre-baseline (2015) and baseline years (2016) (p = .067). The suicide rate is significantly higher in start-up year (2017) compared to the baseline year (2016) (rate ratio=1.67, 95% confidence interval: 1.18-2.36, p = .0039). In addition, the suicide rate for the follow-up year (2018) was significantly lower than that for both the baseline year (rate ratio=0.16, 95% confidence interval: 0.074-0.33, p <.0001) and the start-up year (rate ratio=0.09, 95% confidence interval: 0.046-0.20, p <.0001). On the other hand, the Florida pediatric suicide rate has not significantly changed during the 2014-2017 time period (degree of freedom=3, chi-square value=0.2, p =0.98) but has shown an upward trend.

From baseline year (2014) to follow-up year (2018), the pediatric population within Brevard County ranged from 116,973 to 118,500.

The suicide data was obtained directly from the county medical examiner’s office and from the Florida Department of Public Health.

In an attempt to ensure other relevant external factors were not impacting the suicide rate, we also examined the county unemployment rate, firearm licenses, and census divorce rate which were relatively stable throughout the years examined18,19,20. The 2018 divorce rate was not available at time of this writing.

DISCUSSION

The promising results of this case report illustrate how the health system can serve as a guidepost for a community to address the health needs that matter most to a community. It also demonstrates how the community health needs assessments that health systems and other social service organizations conduct have the ability to shed light on areas where communities are ripe for systemic health intervention7,8.

A critical factor to the success of the implementation of the community wide health initiative was the selection of a health outcome that mattered to the community which was captured within community health needs assessments. This suggests that community health needs assessments performed by health systems can act as windows into the health issues that concern communities most and can act as a catalyst for health initiatives where the health system can partner with the community towards a common goal.

Furthermore, the results of this case report support the previously established notion that the utilization of an evidence based roadmap can make a significant impact on the suicide rate of a population4,5. Unlike previous work, this report suggests that an evidence based technical package targeting suicide can be successfully implemented to target an entire community and does not have to be centralized within a single organization focusing on a subset of individuals. This report also distinguishes itself from prior work in that it was solely focused on a pediatric population.

Given the fact that this health initiative encompassed a portfolio of sub interventions targeting suicide housed within the CDC roadmap, it is difficult to elucidate the impact of each specific intervention towards the final outcome.

Challenges the Task Force has encountered are related to the stigma associated with mental illness. The Task Force continues to address stigma through various messaging campaigns and other interventions. The Task Force hopes to further develop the measures of impact of such interventions.

REFERENCES

- International Initiative for Mental Health Leadership. Zero Suicide: An International Declaration for Better Healthcare. Oxford, UK: RI international. March 2016. https://riinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/zerosuicidedeclaration_2015draft.pdf. March 2016. Accessed June 2019.

- Hedegaard H, Curtin SC, Warner M. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 330. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018.

- Miron O. Suicide Rates Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States, 2000-2017. JAMA. 2019; 321 (23) 2362-2364.

- Coffey CE. Pursuing perfect depression care. Psychiatr Serv. 2006; 57(10):1524-6.

- Coffey CE. Building a system of perfect depression care in behavioral health. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007; 33(4):193-9.

- Dadi E. Florida’s Support for Mental Health Services Fall to 50th in the Nation. Florida Policy Institute. https://www.fpi.institute/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/BM-Mental-Health-Spending-SL22.pdf. February 2017. Accessed June 2019.

- United States Internal Revenue Service. Community Health Needs Assessment for Charitable Hospital Organizations- Section 501(r)(3). https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/community-health-needs-assessment-for-charitable-hospital-organizations-section-501r3. 2018. Accessed June 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Health Assessments and Health Improvement Plans. https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/cha/plan.html. 2018. Accessed June 2019.

- Florida Department of Health. Query tool for Drug Poisoning Deaths. http://www.flhealthcharts.com/charts/OtherIndicators/NonVitalIndDataViewer.aspx?cid=9869. 2017. Accessed June 2019.

- Yarborough BJH, Ahmedani BK, Boggs JM, et al.. Challenges of Population-based Measurement of Suicide Prevention Activities Across Multiple Health Systems. eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes). 2019;7(1):13.

- About 211. http://211.org/pages/about. Accessed June 2019

- DelliFraine JL, Langabeer JR 2nd, Nembhard IM. Assessing the evidence and Lean in the health care industry. Qual Manag Health Care. 2010; 19(3):211-25.

- Pyzdek T, Keller PA. The Six Sigma Handbook, 3rd New York,NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Stone D, Holland K, Bartholow B, Crosby A, Davis A, Wilkins N. Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policy, Programs, and Practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicidetechnicalpackage.pdf. Accessed June 2019.

- Payton JW, Wardlaw DM, Graczyk PA, Bloodworth MR, Tompsett CJ, Weissberg RP. Social and Emotional Learning: a framework for promoting mental health and reducing risk behavior in children and youth. J Sch Health. 2000; 70(5):179-85.

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011; 82 (1):405-32.

- Niederkrotenthaler T, Voracek M, Herberth A, et al. Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther V. Papageno effects. Br J Psychiatry. 2010; 197(3):234-43.

- Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Query tool for Unemployment Rate in Brevard County, FL. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FLBREV3URN. 2019. Accessed June 2019.

- Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Concealed Weapon/Firearm License Holders by County. https://www.freshfromflorida.com/content/download/7502/118869/cw_active.pdf. May 2019. Accessed June 2019.

- United States Census Bureau. Query tool for Marital Status in Brevard County, FL. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_S1201&prodType=table. 2017. Accessed June 2019.